The Use and Meaning of the Eight Directions in Thai Buddhism and Occult Beliefs

In the Royal Institute Dictionary, dated 2542 B.E., the term “ทิศ” or “ทิศา” is defined as meaning “direction” or “side” (referring to the cardinal points such as north, south, east, west, etc.). In poetic language, “ทิศาดร” can be interpreted as “directions.”

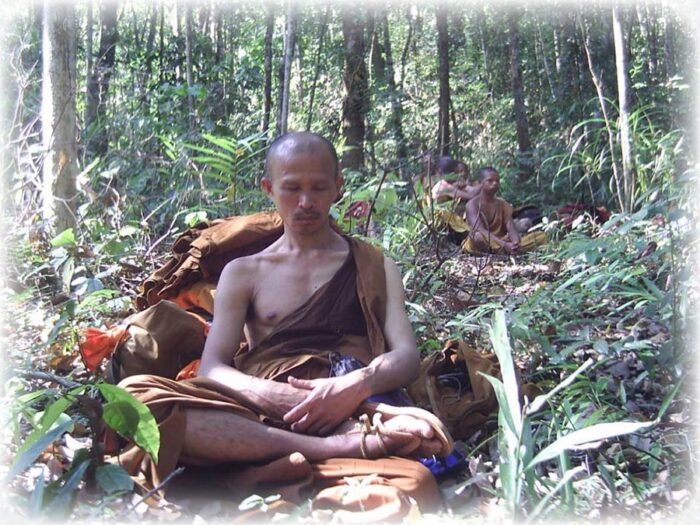

Below; Yant Paed Tidt Sak Yant Thai Temple Tattoo Design

Yant Paed Tidt 8 directional Yantra tattoo design (tiger face version)

-

- Descriptions of the eight directions according to the Royal Institute Dictionary are as follows:

- “อุดร” (Udorn) – The northern direction, also known as “ทิศอุดร” (Northern direction; left side).

- “อาคเนย์” (Ākaneuy) – The southeast direction, alternatively referred to as “ทิศอาคเนย์” (Southeast direction; right side).

- “ทักษิณ” (Taksin) – The southern direction, also denoted as “ทิศทักษิณ” (Southern direction; right side).

- “บูรพา” (Bura-pa) – The southwest direction, also known as “ทิศบูรพา” (Southwest direction; left side).

- In astrology, each of these eight directions is associated with a specific celestial body and represented by a numerical value as follows:

- Sun, associated with the East-Northeast direction, represented by the number 1.

- Moon, linked to the Southeast direction, represented by the number 2.

- Mars, connected to the East-Southeast direction, represented by the number 3.

- Mercury, aligned with the South-Southeast direction, represented by the number 4.

- Jupiter, associated with the West-Southwest direction, represented by the number 7.

- Venus, linked to the North-Northwest direction, represented by the number 5.

- Saturn, connected to the Northwest direction, represented by the number 8.

- Friday, associated with the East-Northwest direction, represented by the number 6.

- Descriptions of the eight directions according to the Royal Institute Dictionary are as follows:

These eight directions are also used in astrology, and have specific celestial bodies associated with them. Each direction is represented by a number.

Astrological Eight Directions and Their Associations:

- Direction: East-Northeast (ทิศอีสาน)

- Associated Celestial Body: Sun

- Represented Number: 1

- Direction: Southeast (ทิศอาคเนย์)

- Associated Celestial Body: Moon

- Represented Number: 2

- Direction: East-Southeast (ทิศตะวันออกเฉียงใต้)

- Associated Celestial Body: Mars

- Represented Number: 3

- Direction: South-Southeast (ทิศตะวันตกเฉียงใต้)

- Associated Celestial Body: Mercury

- Represented Number: 4

- Direction: West-Southwest (ทิศตะวันตกเฉียงเหนือ)

- Associated Celestial Body: Jupiter

- Represented Number: 7

- Direction: North-Northwest (ทิศอุดร)

- Associated Celestial Body: Venus

- Represented Number: 5

- Direction: Northwest (ทิศตะวันตก)

- Associated Celestial Body: Saturn

- Represented Number: 8

- Direction: East-Northwest (ทิศอุดร)

- Associated Celestial Body: Friday

- Represented Number: 6

Explanation:

In astrology, the concept of the eight directions is tied to the belief that celestial bodies have influence and power over various aspects of life and destiny. Each direction is associated with a specific celestial body, and these associations are used in astrological calculations and predictions.

Sun (Number 1): The Sun is associated with the East-Northeast direction. It represents qualities related to vitality, energy, and leadership. People born under this direction may be seen as leaders or have strong leadership qualities.

Moon (Number 2): The Moon is linked to the Southeast direction. It represents emotions, intuition, and sensitivity. Those influenced by the Moon may have strong emotional connections and intuitive abilities.

Mars (Number 3): Mars is connected to the East-Southeast direction. It signifies courage, assertiveness, and action. Individuals influenced by Mars may be assertive and take initiative.

Mercury (Number 4): Mercury is associated with the South-Southeast direction. It represents communication, intellect, and adaptability. People influenced by Mercury may excel in communication and intellectual pursuits.

Jupiter (Number 7): Jupiter is linked to the West-Southwest direction. It symbolizes expansion, abundance, and growth. Those influenced by Jupiter may experience opportunities for growth and prosperity.

Venus (Number 5): Venus is aligned with the North-Northwest direction. It represents love, beauty, and sensuality. People influenced by Venus may have a strong appreciation for aesthetics and love.

Saturn (Number 8): Saturn is associated with the Northwest direction. It symbolizes discipline, responsibility, and challenges. Individuals influenced by Saturn may face obstacles but can achieve success through discipline.

Friday (Number 6): Friday is connected to the East-Northwest direction. It signifies balance, harmony, and relationships. People born on this day may have a natural inclination towards maintaining balance in their lives and forming strong relationships.

These associations provide astrologers with insights into an individual’s character, destiny, and life path based on the direction corresponding to their birth.